1 Student Housing: Executive Summary

Student Housing as an Asset Class

As an asset class, student housing or purpose-built student accommodation (PBSA) has proved to be a resilient, low-risk defensive asset class with a counter-cyclical nature. This is evidenced by the less severe than expected Covid-19 impact on the PBSA asset class. This resilience was driven by lower decline in student demand and an increasing investment appetite. Additionally, periods of economic downturn have historically driven the domestic and international student mobility higher.

Over the last few years, the student housing market has gone global. Whilst historically lead by the UK and US, investment from Western Europe has increased significantly since 2015, whilst growing international demographics in Australia have seen an increasing need for student housing provision. Majority of the source market (students) is dominated by Asia, primarily China and India.

Although the demand for study and housing abroad remains strong, it is shifting by destination and room type and students are also taking longer to confirm bookings this year. Destinations such as Ireland and Spain are showing declines of about 12–20% – while others, such as the US, Germany, and France, have seen volumes fall more sharply (by as much as 75%).

On the pipeline front, the standard pattern of market development has continued even during the Covid-19 crisis. Upcoming student housing projects in Europe and the UK, both under construction and in planning, will offer over 200,000 beds.[1]

Looking forward, unlike other industries, students will need to complete their course work and obtain their degree. They cannot change the institute and will have to continue at the same institution which means that they will need a place to stay. Some costs will also increase since there will be greater pressure on sanitation and cleanliness. If students decide to practice social distancing or operators offer it as a differentiator, they may also see lower occupancy.

On the investment side, a growing variety of pension funds, institutions, and insurers actively invest in student housing. These institutions, many of which invest internationally, accounted for around half of all student housing investment volume between 2011 and 2018.

Student housing yields average 4.8% across 15 key national markets, 370 bps above bonds. They range from 6.0% in Australia (4.11% net of bonds) to 3.7% in Germany (3.70% net of bonds).[2]

Student Housing Market in Africa

A continent-wide trend is the demand for accommodation from the mounting number of university students throughout Africa. There were an additional 2.5 million students in tertiary education in 2017 compared with 2012, according to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics – a 21% increase.

This is a consequence not only of increasingly youthful populations, but also the commitment to raise the university participation rate as a way to increase economic growth and reduce inequality. Over the next five-year period student numbers are likely to continue increasing significantly. An additional 72 million Africans will be aged 15–24 by 2028, with the highest growth – 13 million – in Nigeria.

Additionally, there is growing compulsion for institutions to provide accommodation to maintain their university status. There is already a requirement in Kenya to own land and this will soon be enforced in Zambia and Uganda.

The demand for purpose-built student accommodation (PBSA) in SSA is growing rapidly, and is starting to attract interest from investors, private operators, and developers from around the world. Within this environment, student housing in certain SSA regions is set to emerge as an attractive alternative investment category, just as it has in developed markets such as the UK and US. Non-cyclical rental levels, stable yields, limited supply, and growing demand driven by demographic trends and positive economic prospects all make the asset class highly attractive to institutional investors.

The general need for affordable and inhabitable housing is evident now more than ever. While most African country governments already had plans for affordable housing in place, implementation of those plans is expected to pick up pace now. A quickly increasing student population coupled with the need for affordable housing is expected to drive the demand for PBSA market in Africa. However, certain challenges such as supporting infrastructure shortages, affordability and financing, lack of foreign students, and political instability remain to be addressed.

Student Housing in Senegal and Ivory Coast

The Republic of Senegal has been among Africa’s most stable countries, with three major peaceful political transitions since independence in 1960. The country is also the second fastest growing economy in West Africa. It also offers a competitive destination for investments in Africa on account of its political stability, strategic geographical position, access to sub-regional markets and improving infrastructure.

In Senegal, the constitution requires and guarantees that every child receives education. Education in Senegal is free and compulsory until the age of 16. Since 2000, the nation has made significant headway in improving primary school enrollment rates— raising it from 69% to a steady 82% in 2019.[3] However, the difficulty is in retaining students: many are discouraged from continuing education after the primary level because of untrained staff, challenging school environments and resource shortages.

Senegal’s youth population is exceptionally large, with those 14 and under accounting for 43%[4] of the total population. Historically, Senegal has struggled with the prospect of developing human capital. The high influx of youth coupled with widespread poverty has left more than 30%[5] of the total population illiterate in recent years.

Despite high illiteracy rates, a significant opportunity exists for student housing in Senegal. In 2014, President Macky Sall launched the Plan Senegal Emergent (PSE, Emergent Senegal Plan). As a part of PSE, the government was seeking US$280 million to build several student housing facilities as university residences to be built at six locations with a total accommodation capacity of 40,000.

As of 2015, student population of all these universities put together was about 16,000. With the construction of the new university (Université Sine Saloum), this number is expected to reach about 44,000. This creates an unmet housing demand of 28,000 beds.[6]

Côte d’Ivoire gained 12 places in the World Bank Doing Business 2019 ranking (110 out of 190 countries). In addition to making the business environment more attractive, the country has also improved its infrastructure. The momentum to maintain a sustained growth regime over the medium term remains.

Despite its recent macroeconomic achievements, the country’s human development and other social outcomes are still below those of most countries with comparable per capita income. In the 2018 United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Human Development Index, Côte d’Ivoire ranked 170th of 189 countries. Average years of schooling are 7.7; whereas the regional average is 8.2. Under-5 mortality rate is 88.8 deaths per 1,000 births (2017), against the SSA average of 83.2. Ivoirian life expectancy at birth is 53.5 years (2016), compared to 58.1 in SSA. Côte d’Ivoire’s Human Capital Index is 0.35, below the average of 0.40 in SSA.

Education sector was disrupted nationwide during the political crisis between 2002 and 2011, leaving many children and youth unable to attend school. Enrolment rates remain low past secondary levels. As of 2019, children who start school at age 4 can expect to complete only seven years of school by their 18th birthday, below the Sub-Saharan Africa average. While the primary gross enrolment rate (GER) was 99% in 2017 – up from a low of 68% in 2006, low transition rates led to an overall secondary GER of 50% with a sharp drop in enrolments in upper secondary.[7] Overall, literacy levels amongst youth have also remained unchanged for decades, hovering around 50%. The university sector was particularly affected by the crisis – tertiary GER declined from 9.3% in 2005 to 8.3% in 2016, compared to an average of 24.4% for lower-middle-income countries.

Further, according to World Bank’s 2017 report states that 63% of Ivorian students finish primary school compared with 72.6% in Africa and 92.8% in middle-income countries. Those who do complete primary school have lower literacy and math skills than fellow students in other French-speaking African countries with, for example, a math score of 476 in Côte d’Ivoire as opposed to 594 in Burundi. Moreover, less than half (44%) of the population over the age of 15 was able to read and write in 2015, compared to rates of 77%, 60% and 56% in Ghana, Nigeria and Senegal, respectively. The gaps widened in secondary school, with girls, children living in rural areas and low-income families being the most affected.

The government has, since 2012, invested heavily in rehabilitating the basic education sector, by building new classrooms and hiring teachers, and made improving educational outcomes a strategic priority in its National Development Plan. The government has increased its total education budget by 7.5% annually. In line with international norms, the government spent a quarter of its budget, or nearly 5% of GDP, on education. As a result, education outcomes are improving quickly: enrolment rates have been growing since 2015 at all levels (with structural pressures at higher levels). However, it will take several years for the K-12 “flow” to be near that of comparator countries. Improving learning will probably be the most difficult to achieve in the short term. The urgency of educational restructuring is closely related to the country’s youth bulge – in 2018, 42% of the population was under the age of 15.

The government aims to continue investing in the enrolment and completion of primary education. To this end, CFA 875.5bn (€1.3bn) was allocated to the 2016-20 PND to help achieve universal, inclusive and quality primary education. Meanwhile, CFA 259.3bn (€389m) was budgeted for secondary education development, focusing on infrastructure rehabilitation, construction and personnel hiring.

Looking at the Housing market, although construction of a wide range of commercial units and high-value projects have been completed since 2011, there is a housing shortage of 400,000-600,000 units across the country, with around 200,000 of these in Abidjan alone. As the population and urbanisation rates grow, demand for housing is rising by an estimated 40,000-50,000 units per year.

There has been a persistent shortage of student housing in Abidjan. For years, university residences were used to house soldiers who arrived during the 2011 post-election crisis to fight forces loyal to former president Laurent Gbagbo. But many remained even after the conflict ended, and moved out only in recent years, leaving behind deteriorating buildings.

Outlook for Student Housing in Senegal and Côte d’Ivoire

Despite the fact that the PBSA asset class is still at a very nascent stage, consultations with the key industry and public sector stakeholders have highlighted the following strong attributes of the sector:

· Resilient performance in downturns, as evidenced in developed markets (and more recently during COVID-19 lockdowns)

· High occupation rates as evidenced in established markets across the world and as noted among almost all large operators in SSA

· Relatively stable income and strong above-inflation rental growth prospects

· Constant and growing imbalance between supply and demand

· Favorable demographics

· The government’s stated policy to address affordability issues through supportive policies and give an impetus to the education sector

While there are still uncertainties and by extension higher levels of perceived risk, there is a real will to address some of the challenges by both the public and the private sector, to close the supply demand gap and to support human capital development in both Senegal and Côte d’Ivoire. Investors and funders are weighing the risks against the advantages and benefits of early entry, along with the other more general appealing attributes of student housing.

2 Student Housing as an Asset Class

As an asset class, student housing or purpose-built student accommodation (PBSA) has proved to be a resilient, low-risk defensive asset class with a counter-cyclical nature. This is evidenced by the less severe than expected Covid-19 impact on the PBSA asset class. This resilience was driven by lower decline in student demand and an increasing investment appetite. Additionally, periods of economic downturn have historically driven the domestic and international student mobility higher.

2.1 Global Student Housing Investment Volumes

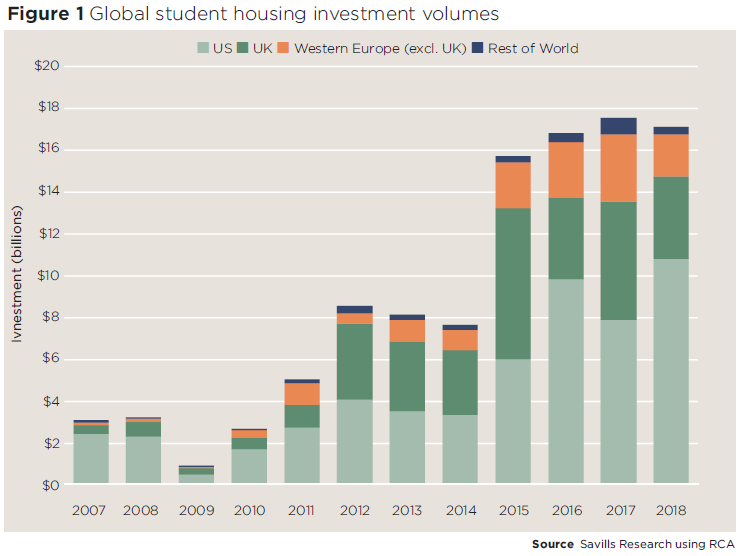

Global investment into student housing totalled $17.1bn in 2018. However, total volumes were still up 425% since 2008, as compared to a 130% increase in the global real estate volumes over the same period.[8]

Source: Savills Research

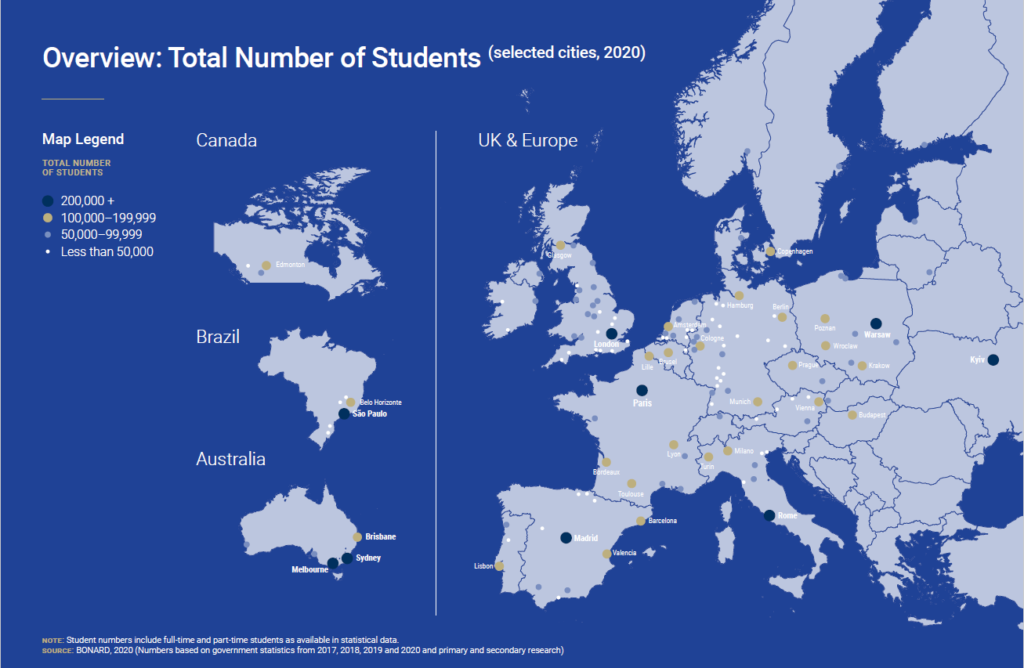

Over the last few years, the student housing market has gone global. Whilst historically lead by the UK and US, investment from Western Europe has increased significantly since 2015, whilst growing international demographics in Australia have seen an increasing need for student housing provision. Majority of the source market (students) is dominated by Asia, primarily China and India.

Source: BONARD Research

Although the demand for study and housing abroad remains strong, it is shifting by destination and room type and students are also taking longer to confirm bookings this year. Traffic and booking data indicated a drop in international demand for student housing this year, with the decline varying considerably from destination to destination. Destinations such as Ireland and Spain are showing declines of about 12–20% – while others, such as the US, Germany, and France, have seen volumes fall more sharply (by as much as 75%).

Most of the universities are now open to students and the country governments are supporting the same by expediting the vaccination for their foreign bound students. A study by research firm BONARD reveals that private student housing providers have created Covid-19 contingency plans, secured their premises, and offered reassurance to both students and their parents. The pandemic saw demand shift to non-shared units, with some operators renting double rooms as singles to comply with regulations as well as to meet student demand.

On the pipeline front, the standard pattern of market development has continued even during the Covid-19 crisis. Upcoming student housing projects in Europe and the UK, both under construction and in planning, will offer over 200,000 beds.[9]

2.2 Impact of Covid-19 on PBSA

Amidst the political, social and economic uncertainties of the COVID-19 pandemic, real estate and alternate real estate asset classes have been impacted to varying degrees. One of the asset classes that has attracted significant investment in the last three years has been student housing. Investment in this asset class was driven by market potential (shown by a constant demand-supply imbalance) and relative stability of cash flows and higher yields.

Student housing operators and aggregators tapped into this market and invested in setting up larger facilities with many amenities and varying degrees of technology intervention. Overall rental yields (10-15% compared to 8-10% for commercial office assets) were also better than in other asset classes on a risk adjusted basis. Risks were considered to be lower since education was considered recession proof and low churn rates made for steady cash flows.

The current situation of COVID-19 has resulted in major changes affecting all four stakeholders — the colleges/educational institutions, students, asset owners and the student housing providers/managers.

Though the student housing operators did see an impact, the quantum was more manageable compared to some other real estate classes.

Looking forward, unlike other industries, students will need to complete their course work and obtain their degree. They cannot change the institute and will have to continue at the same institution which means that they will need a place to stay. Though some may try to economical and go back to shared stays compromising on the amenities. The operators may however lose out on three to four months of revenue due to the delay in commencement of the academic sessions. Some costs will also increase since there will be greater pressure on sanitation and cleanliness. If students decide to practice social distancing or operators offer it as a differentiator, they may also see lower occupancy.

2.3 Key Market Players

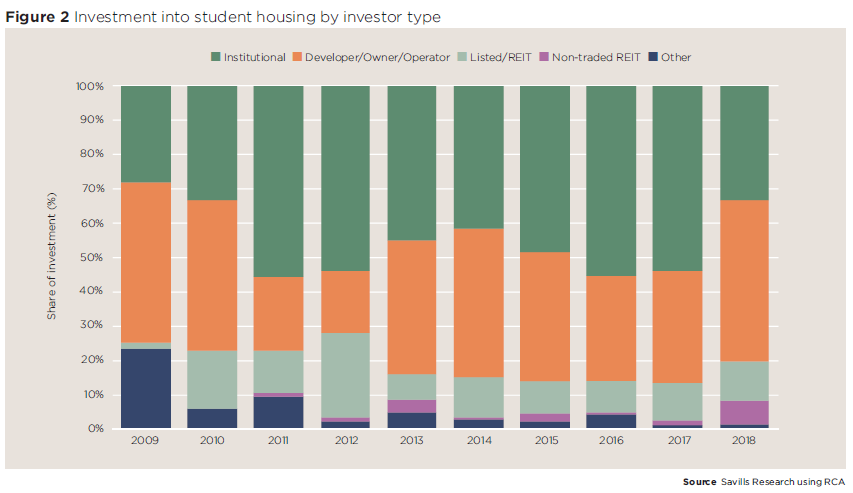

As student housing has matured as an asset class, the types of businesses investing in the sector have changed. At first, pioneer developers held and operated their own stock. Later, sovereign wealth funds and private investors began buying stock as their appetite for alternative assets grew.

Now, a growing variety of pension funds, institutions, and insurers actively invest in student housing. These institutions, many of which invest internationally, accounted for around half of all student housing investment volume between 2011 and 2018.

Source: Savills Research

Top Investors in Student Accommodation since 2016[10]

Sr. No. | Investor | Notable JVs | Type | Origin | Portfolio Geography | Total Volumes (2018 US$ mn) |

1 | Greystar | Chapter – Greystar, Allianz, PSP Investments | Developer/Owner | US | US, UK, Spain, Netherlands, Austria | 4,500 |

2 | GIC | Scion Student Communities GIC, CPPIB and Scion Group | Sovereign Wealth Fund | Singapore | UK, US, Germany, Australia | 310 |

3 | CPPIB | Scion Student Communities GIC, CPPIB and Scion Group | Pension Fund | Canada | UK, US, Spain, Germany | 310 |

4 | Scion Group | Scion Student Communities GIC, CPPIB and Scion Group | Developer/Owner | US | US | 540 |

5 | Harrison Street RE Cap |

| Equity Fund | US | UK, US, Germany, Ireland | 220 |

6 | Mapletree Investments |

| Investment Manager | Singapore | US, UK, Canada | 200 |

7 | Brookfield AM |

| Real Estate Operating Company | Canada | UK, US, France | 830 |

8 | Goldman Sachs | iQ Student Accommodation (Vero Group) – Goldman, Wellcome Trust and Greystar (minority), Atira | Equity Fund | US | UK, US, Australia | 250 |

9 | BREIT |

| Private REIT | US | US | 1,200 |

10 | GSA Group |

| Developer/Owner | UK | Germany, Ireland, Spain, UK, Australia | N/A |

2.4 Asset Yields

Overall yields have decreased as the sector has matured and attracted a deeper pool of investors. Less developed countries still present opportunities for yield-seeking investors. In markets such as India and Africa, where student housing is much less mature, there is potential for yields to decrease further. However, even in more mature markets where student housing appears more fully valued, the sector still offers returns well above government bonds.

Student housing yields average 4.8% across 15 key national markets, 370 bps above bonds. They range from 6.0% in Australia (4.11% net of bonds) to 3.7% in Germany (3.70% net of bonds).[11]

Region | Q1 2019 Prime Net Student Housing Yields | 10-year Government Bonds | Yield Net of Bonds |

Australia | 6.00% | 1.89% | 4.11% |

Austria | 4.25% | 0.31% | 3.94% |

Denmark | 4.00% | 0.08% | 3.92% |

France | 4.25% | 0.37% | 3.88% |

Netherlands | 4.75% | 0.19% | 4.56% |

Germany | 3.70% | 0.00% | 3.70% |

Ireland | 4.75% | 0.61% | 4.14% |

Italy | 5.50% | 2.54% | 2.96% |

Norway | 4.00% | 1.72% | 2.28% |

Poland | 6.00% | 2.87% | 3.14% |

Portugal | 5.50% | 1.26% | 4.24% |

Spain | 5.00% | 1.12% | 3.88% |

Sweden | 4.25% | 0.38% | 3.87% |

UK | 4.50% | 1.10% | 3.40% |

USA | 5.80% | 2.51% | 3.29% |

2.5 Investment Highlights

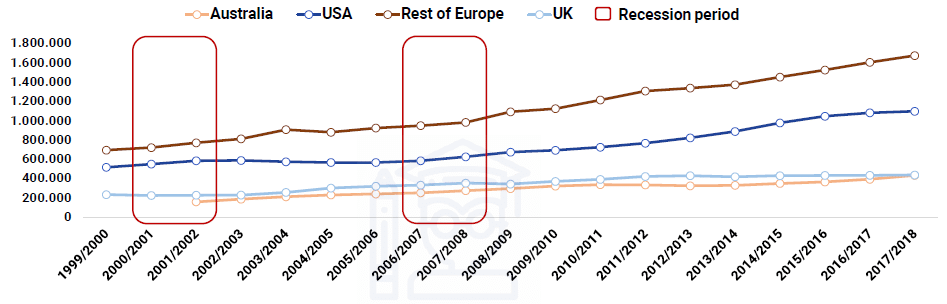

· Hedge against slowdown: Student housing’s counter-cyclical income stream attracts global institutional investors. In economic downturns, demand for student housing tends to increase as students prolong their studies while they wait for the job market to improve, while those out of work return to university to upskill

Number of international higher education students in selected destinations[12]

· Increasing international student mobility: Between 2007 and 2017 the number of internationally mobile students grew by 64% to over 5 million, according to UNESCO. The US, UK and Australia are host to the largest number of them. Future growth in outbound student numbers is expected to continue to be driven by major source markets China and India. Their rate of growth is forecast to slow to 1.7% per annum by 2027, however, from an average of 6% between 2000 and 2015, according to a British Council report

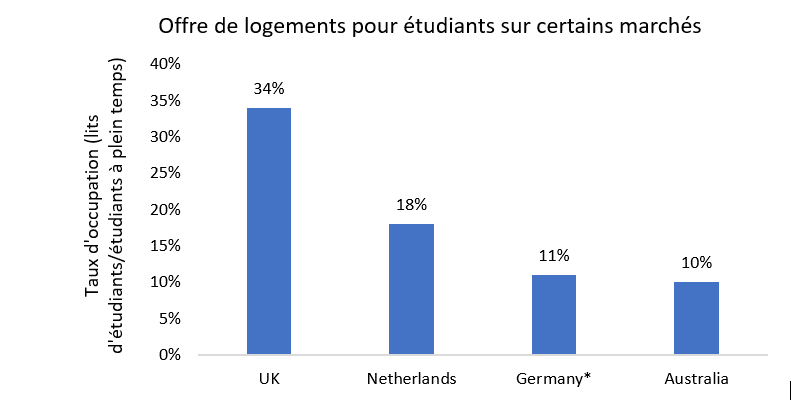

· Low supply: Despite a rise in student numbers, and in turn investment, student accommodation remains largely undersupplied at the national level. Student housing provision rates (number of beds / full time students) in major markets range from 34% in the UK to just 10% in Australia

*Top 30 cities. Source: Savills Research

· Opportunity in the middle tier: So far, developers and investors have focused on the premium end of the market. There exists significant potential in serving the middle tier between low-quality university stock and new premium product.

· Beyond students: Moreover, experts are predicting significant opportunities in co-living and build-to-rent models for future graduate populations, building on the existing student appetite for particular services and facilities in accommodation. The co-living model mixes students with other occupiers. This broadens the demand base as well as supporting a wider range of services and amenities, in turn enhancing the appeal to occupiers. Whether developers decide to put a foot forward in terms of mixing the two populations is yet to be seen, but it appears the most likely hybrid to stem from the evolving market.

[1] BONARD Research

[2] Savills Research

[3] World Bank

[4] UNESCO

[5] UNESCO

[6] Government of the Republic of Senegal

[7] EdStats

[8] Savills Investment Management

[9] BONARD Research

[10] Savills Research

[11] Savills Research

[12] Institute of International Education, UNESCO Institute for Statistics, Australian Government Department of Education, Skills and Employment, BONARD Researc